Welcome to Transgressor,

a celebration of outsider philosophies

and cultural trespassers. The following pages contain

video, audio and other interactive features. The table of contents

is the main navigation page for the issue; click or touch

the triangle icon below to return at any time.

Please tell us what you think:

feedback@transgressormagazine.com

booksBoy with Grasshopper in his TeethLife as a Dreamy Little Fucker from Pocatello, IdahoWords by: Tom Spanbauer

Photos courtesy of: Tom Spanbauer and Sage Ricci

musicLet’s Give it Our AttentionThe Work of Lee RelvasInterview by: Scott Tankersley

Images and video courtesy of: Lee Relvas

inspirationRough CutsIn Search of Questions with HyenazInterview and videos by: Igor Siddiqui

Cut-ups courtesy of: Hyenaz

sportsEverything Looks Like a Punk ShowThe Resurgence of NOLA’s Renegade Skate ParkWords by: Clark Allen

Images by: Clark Allen, Aubrey Edwards, Brad McCormick, and Julian A.

Video by: Justin Gordon

sexPassing ThroughTrue Stories of Sex on the RoadWords by: Silky

Images by: Autumn Spadaro

Starring: Silky, David, Cody, Nevah, and Gorgi

travelBiking to BukharaA Day in the Life of Eleanor MosemanWords and images by: Eleanor Moseman

meditationA Study in Personal Expansionwith Acid Sweat LodgeVideo by: Acid Sweat Lodge

Music by: Stephen Hamm

fetishGone to the Forest to Look for WoodHazel Hill McCarthy on the Voodoo of Genesis P-OrridgeInterview by: Diana Welch

Images by: Hazel Hill McCarthy III, Douglas J. McCarthy, Lewis Teague Wright, Drew Denny, and Eric Nordhauser

Starring: Genesis BREYER P-Orridge, Dah Dgbeninon, Sardou (Emmanuel) Dgbeninon, and Hypolite Apovo

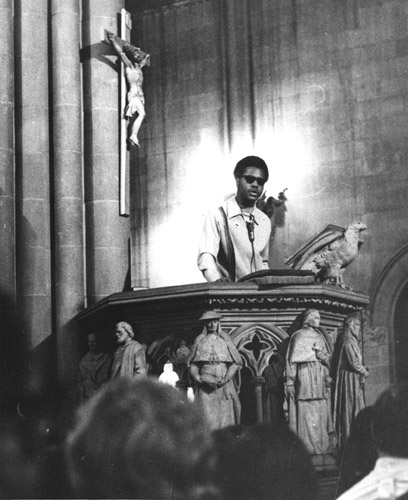

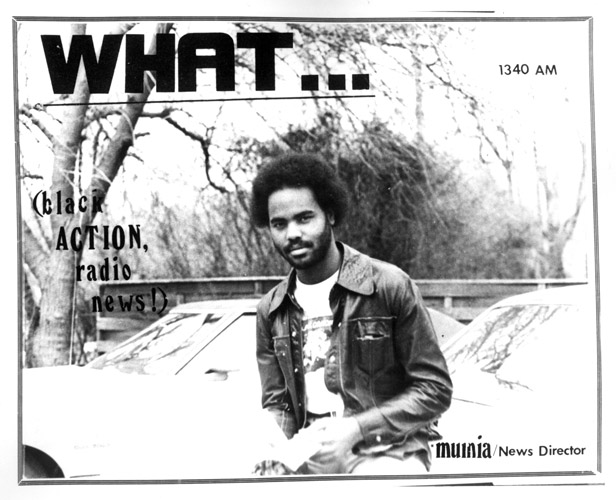

transcendenceA LIfe Beyond BarsMumia Abu-Jamal and the Power of ConvictionWords by: Rebecca Bengal

Images and audio courtesy of: Mumia Abu-Jamal and Stephen Vittoria

editor Diana Welch

contributing editorsRebecca Bengal, Aubrey Edwards, Igor Siddiqui, Justine Kurland

copy editorKaty McElroy

publisherMorgan Coy

art directionRyan Rhodes

built byChris Bauman

The product of drunken conversations, late night parties, trips to the woods, high times, and long trips down the highway.

Organized for the increase and dissemination of outsider knowledge.

Since 2007 the Acid Sweat Lodge has supported various explorations and research projects, adding immeasurably to freedom of thought, patterns of fraternal interaction, and aspects of the future.

Transgressor Contributing Editor Aubrey Edwards is (primarily) a portrait photographer and educator, and spearheads the all female photography collective Southerly Gold. She is also a certified Louisiana Master Naturalist, wild bird rehabilitator, the Den Mother of the Crescent City Vintage Motorcycle Club, and once went home with a twice Academy Award nominated Hollywood heartthrob.

Presently, she is working on a collaborative ethnographic film and accompanying multimedia website detailing the birth of the African American skateboard community in post-Katrina New Orleans, and the social/political challenges this new subculture are presently facing.

In 2010, she partnered with the Smithsonian-affiliated Ogden Museum of Southern Art to create the collaborative archive Where They At: New Orleans Bounce and Hip Hop in Words and Pictures, featured in Transgressor No. 1

Photographer Autumn Spadaro has been using a darkroom and a 35mm camera since she was eight years old. She is a graduate of the School of Visual Arts in NYC and a co-founder of Common House in ATX.

Brad is a recent high school graduate from Sci Academy in New Orleans East. He has a lot of passion for photography and a unique personality that people love about him. He is presently working on a collaborative ethnographic film with his photo teacher, Aubrey Edwards.

Clark Allen is a punk living in New Orleans.

Writer, reporter, and editor Diana Welch founded Transgressor with Monofonus Press in 2011. Her work has been featured in the Austin Chronicle, Vanity Fair, People Magazine, Good Morning America, The Diane Rehm Show, and elsewhere.

She lives with her partner and son in Austin, Texas.

You can see more of her work here.

Transgressor Contributing Editor Igor Siddiqui is an architect, scholar, and artist. His work has been exhibited and published internationally. He is the founder of ISSSStudio and an assistant professor at The University of Texas at Austin. Siddiqui co-edited Transgressor No. 3.

Julian A. spends most of his time skateboarding in parking lots and at Parasite Skatepark. He will be an eleventh grader next year at Sci Academy in New Orleans East. He is presently working on a collaborative ethnographic film with his photo teacher, Aubrey Edwards.

Justin Gordon was one of the first skaters to come onto the New Orleans scene just after Katrina. He came up in the East but now lives in the historic Treme neighborhood in New Orleans 7th Ward. He is one of the best skaters in town.

Transgressor Contributing Editor Rebecca Bengal is a writer and photographer whose fiction and nonfiction has appeared in Best American Nonrequired Reading, The New York Times, The Paris Review Daily, and The New Yorker online.

She wrote about New York’s last waterfront pioneers for Transgressor No. 1.

Scott Tankersley is a student (CUNY), queer activist, aspiring musician, and drama queen who currently resides in Brooklyn, NY.

Silky is an artist, performer, and organizer currently living in Austin, Texas.

Words by Tom Spanbauer

Photos courtesy of Tom Spanbauer and Sage Ricci

As a horribly lonely 14-year-old girl in rural Virginia, I found a book called The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon and, simply put, it made me feel less alone. This sense, this promise of belonging, stuck with me long after I had forgotten the name of the man who created the work that had meant so much to me. It was a new feeling, subtle and hungry, and I have been feeding it ever since.

Twenty years later, I found myself in a conversation with a friend about book called In the City of Shy Hunters. “No one’s work is as important to me as Tom Spanbauer’s,” she said to me passionately, almost woefully, as she listed his work. In that moment, I realized that the man who wrote a book that changed my friend’s life was the same man who wrote a book that had changed mine. I immediately set out to read everything he’d ever written, including the short but powerful Faraway Places and the classic coming of age tale Now is the Hour. I wrote to him and told him what his work meant to me, and I asked him if he’d be interested in doing something for this magazine. He wrote back to say yes and mentioned that he had a new book coming out, I Loved You More. He offered to have his publisher send me a copy. She did. It’s epic.

After Tom agreed to collaborate on a profile for this issue, I sent him a bunch of random questions. He wrote back pages filled with depth and wisdom that spanned his entire life. What follows is part of what he wrote to me, edited and condensed. Because of space considerations, I had to take out a bunch of great stuff, such as the first time Tom fell in love with a man while he was in the Peace Corps in Kenya; his sorrowful regrets about how he treated a friend called Sam; meeting and marrying and leaving his ex-wife; and his thoughts on drag.

What’s left is a glimpse into the life of a man who may have been born into a family that didn’t understand him but who has gone on to create a family of admirers and peers who are profoundly inspired by his quest to understand himself.

- Diana Welch

My mother’s family spoke Hochdeutsch and lived in a brick house. My mother’s father was a gentleman farmer who read Goethe and Schiller and called his daughters wilde Madchen. My mother’s father died during the depression when my mother was a young girl. There were seven children.

My father’s family spoke Plattdeutsch and there were eight children. My father’s father, Joe, was the town drunk. He was also the garbage collector and he cured meat and had honeycombs. A friend of my family once told me that when he was a little boy at midnight mass at St. Veronica’s in Blackfoot, Joe stumbled in late and very drunk. Halfway up the main aisle he dropped his bottle of moonshine.

My mother was an ideal young woman, a virgin and a romantic, and she had very high expectations when she married my handsome father. But the way she told it: “My mother gave us a milk cow and we tethered that cow to the fence outside your father’s parents’ house. Your father and I moved into the lean-to of that house. The next morning I woke up and started cleaning and cooking for your father and his mother and his father and since then it has never stopped.”

Stupid Hick was what my mother called my father.

My sister Barbara was born first and three years later I was born. Right off, I was my mother’s boyfriend. The prince who had arrived to save her from monotony and servile work. My father sensed somehow that I was on her side, or that I wasn’t on his, or maybe he just didn’t like me. Perhaps I was too effeminate of a boy. I know I was a very exuberant boy. Whatever the case, however it started, my father and I were always enemies.

One time when I was three or four I really thought he was trying to kill me. He lay on top of me on the front room floor and I couldn’t breathe. I remember I was screaming. I tried to reach to the corner of the carpet, just something to reach for, I didn’t know what, just a way to keep living and breathing.

When I was four and a half, my mother gave birth to my brother Russell. Russell was hydrocephalic. He lived for seventy-seven days. I don’t think he ever stopped screaming. My first published short story was called Sea Animals and it’s all about Russell’s death. That story is also a part of Now Is the Hour.

Russell’s death was monumental. It seems Russell’s death was when I first started being aware of myself. When he died my mother told me he fell asleep.

I’ve had issues with sleep all my life.

My sister wanted me to be a girl. A playmate she could play house and dolls with. My father was hardly ever around during the day, so my sister and I played dress-up. My mother knew I was playing dress-up with my sister. In fact, there were times when we all played dress-up together. I remember one time, I was five years old, we were all “having tea”—cucumber sandwiches and all. All of us dressed up as “movie stars.” My father drove in unexpectedly and my mother and my sister ripped off the dress I was wearing and put me in the back bedroom with a toy truck in front of me.

Then there was the time when my sister was in school and I asked my mother if I could play dress-up by myself. She told me it was OK, so I went down to the basement and opened the dress-up trunk—a steamer trunk full of all those magic colors and fabrics. There were sparkling jewels and lipsticks. I was in full drag when a strange man came down the stairs. He was yelling at me. I don’t remember what he was yelling but he scared me to death. Something about not being a real boy and if your father could see you he would be so ashamed. This man, from our church, started batting me about and he tore the dress I was wearing off me. He left me lying on the basement floor with my hands covering my head.

It turns out my mother called this man up and asked him to come over and scare me so I would stop acting like a girl.

My mother had two passions. First and foremost was Catholicism. In the middle of the day, at the end of the day, whenever or wherever, in the middle of the field, on the drive to Blackfoot, my mother would bring out the rosary and we’d pray to the virgin. I wish I had a dollar for all the rosaries I’ve prayed. She also made novenas to Our Mother of Perpetual Help. Every Tuesday night we’d drive the twelve miles to town for Our Mother of Perpetual Help devotions. I can remember one line of a prayer during that service. It was “I who am the most miserable of all.”

That was me alright.

My mother’s other passion was playing the piano. She could play by ear and there were many nights in my childhood when we sat around with my cousins and aunts and uncles and sang all the old songs. Melody of Love, Stardust, There Is a Tavern in the Town, Du Du Liegst Mir Im Herzen, Little Brown Jug. I think my mother was most herself when she was playing the piano.

The boy with the grasshopper on his teeth was in many ways a slave. From the time I was twelve until I was twenty-two, every summer, twice every summer, I baled one hundred acres of hay, hauled the hay, and stacked the hay. In many ways the rage in me was formed in those teenage years, standing in hundred-degree weather in the hot sun, covered with a quarter inch of hay dust, standing behind the baler, waiting for another bale to come out. The way I was indentured, the way I was stuck into that humiliating, uncomfortable, repetitious hard labor day after day after day, year after year, something broke in me. I hated my father to such a degree. I hated my life. I hated myself. I hated that I was enslaved, yet I hated that I was too terrified to step out on my own.

When my brother was born, they named him John Jr. At last my father could have the son he wanted. And John was just like his dad. And at last I had somebody I could beat on. For one who’s felt bullied all his life, I must say when it came my turn I beat on him every chance I could get.

I was so lonely I decided to buy a book and write down in that book only things that were true. I called it the Truth Book. It was a leather book whose pages were gilded. I wrote down on the first page TRUTHS: Billie Cody has big tits. I think Karl Kameron is queer. And I masturbated three times today.

When I stopped and read what I had written, it was like alchemy. Suddenly all that stuff that was inside me was outside me. Somehow those things became things. Things other than me. What a relief.

Of course my mother found the book. One night, after working as a busboy at the Holiday Inn, I came home late and I opened the refrigerator door and was pouring myself a glass of milk. My father came running out of my parents’ bedroom and yelled: You take that thing you call a truth book and you get the hell out of this house. And don’t you ever come back. But first go into that bedroom and apologize to your mother. My father had yelled at me before, and I had regular beatings on my bare ass with a belt, but he’d never told me to leave the family. My parents’ bedroom smelled of his old socks and beeswax. My mother was lying on the bed screaming: You’re going to hell! You’re going to hell! And I knelt down and prayed the rosary for my soul. I remember thinking: Why did I say those awful things. What’s wrong with me?

I needed to get my ass out of that house. I moved into a fraternity house, in the attic. I started getting good grades in school. I worked two jobs and paid for myself. My last three years of college, I took incredible literature classes, philosophy classes, German classes, French classes. I was reading Goethe and Schiller. Hell I was reading Voltaire. I was in fucking heaven. In all three years I got one B and the rest were A’s.

At my university graduation, my father forgot the camera.

As soon as I left Idaho, as soon as I left the town I was raised in, as soon as I left my father, I went to the place of my father’s deepest racist fear. Black Africa.

It’s quite difficult to talk about Africa. My next book is about Africa and my time in the Peace Corps. I tend not to understand things well until I’ve written about them. Africa has had such a huge influence on me it’s hard to assess. I’m not sure I can do Africa any justice by writing a couple of paragraphs about it.

I met my native brother, Clyde Hall, just when I returned from the Peace Corps in 1971. I got a job at Idaho State University as a counselor in an outreach program. I was given the job to be the advisor to the Indian Club. It was such a ridiculous posting for me. When I returned from Africa, it was such a surprise to see native people all around me. Before Kenya, of course all those native people were there in Pocatello right alongside of me, but I somehow had managed not to see them. And now here I was given the job as Indian Club Advisor.

I was standing in the Indian Club library, ostensibly categorizing books alphabetically, but really I was hiding. I didn’t have the faintest clue on how to approach any of the Native American students. So I was hiding in the library. Really I was reading Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

I was standing on a ladder and I was wearing a green pair of corduroys, 70s style, tight-fitting waist, no back pockets, and bell-bottoms. I didn’t hear the young man enter the room because I was so engrossed in the book. Then I heard: “Where did you get those pants?”

Thus began one of the most important friendships of my life. A friendship so strong that we cut one another’s wrists and promised brotherly love to one another forever. I like to joke that all this Indian spirituality began with how my ass looked in a tight pair of green corduroys, but that’s exactly how it began.

As it turns out, Clyde and I had lived parallel lives. He on one side of the reservation line, me on the other. In fact, my father’s farm bordered the Fort Hall Indian Reservation on two sides. We’d never actually met that we could remember, but we recognized each other right off. He was Shoshone-Cree and I was a white man but we were both gay. We just didn’t know it yet. Or let’s say admit it.

I was able to help Clyde out with some minor things, scholarships, and grant applications and such. But the real teacher was Clyde. That day in the library we sat down and started talking, and here we are forty-three years later, still talking.

One day I was walking through the cemetery and one tree began to shake with a strange wind. No other trees were moving. I told Clyde about it and that same day he had me talking to that tree and giving the tree a gift of tobacco and a piece of red cloth.

Slowly with Clyde’s instruction, a truth began to disclose itself: The earth is our mother and everything in it has an awareness and is alive. This was such good news for my Western mind. Things started to make sense. The earth was alive, nature was alive, and by stepping into myself, I was stepping into nature.

Everything seemed to bloom.

Then one day walking across the ISU campus, I saw a bull elk standing in the middle of the football field. I stopped in my tracks because it was such a magnificent creature and I’d never seen a bull elk up close like that. The elk tossed his end and his rack of antlers then walked into the underbrush of a nearby stand of trees. I went crazy, telling everyone there was an elk on campus. But no one else had seen the elk. When I spoke to Clyde about what I had seen, Clyde told me that elk was a very important animal for me and to pay attention to what elk means. And as far as I can tell from over the years, what elk seems to embody is someone with great physical beauty and strength but doesn’t really know it.

So much of what is termed as “magical realism” in my books has come from what I’ve learned from Clyde. He opened his arms and let me into his world. I was present at a feast from his grandfather, Alasandro, and his adopted father George Wesaw. I took part in sweat lodges, I danced with a very holy pipe in Montana. All these things brought me to a deep spiritual understanding. And did I mention, Clyde had a great deal to do with me coming out. So in that sense, Clyde and my green corduroy pants just proves everything I’ve learned from Clyde to be true. Even those green corduroys are alive.

At the restaurant I was working in, in Boise in 1978, it seemed like there was something in the water. All my fellow friends and employees started turning up gay. The last straw really was my friend Will. Will and I had had become avid “junkers,” driving all over Idaho looking for old junk, clothes, artifacts. Every object in Will’s house was really something else. His ashtray was a wagon wheel. His salt and pepper shakers were chickens, his chair was alligator.

I remember the day, as I was driving down the ramp in Meridian onto I-5, I said to Will, “Yes, I’ve often thought about having sex with men.”

Looking back on that day with Will now, I can see how untruthful I was. Because, after all, I had fallen deeply in love with a man in Kenya only eight years earlier. But the love I’d felt for James I’d somehow made disappear because it was just too painful. So on this day with my friend Will, what I said was all that was possible for me to say.

All this ends up with me leaving my wife Evie and driving my pickup across the United States to live with a friend in New England. Two years later I move to Key West. Key West is another place I haven’t written about. Like Africa, there is so much that I know, but I don’t know really yet, because I’ve never written about it.

Will moved to Key West as well, along with our friend Leo. Really, I guess all I can say about Key West at this point is that it was a training ground for Manhattan. I moved to Key West to find my gay brothers and sisters, to talk and drink and love one another. I moved to Key West to learn to be gay. What I found was quite different. The end of the road in the early 80s, AIDS already apparent in several mysterious deaths. I don’t want to be too harsh, but what I found in Key West was mostly rage. What my gay brothers and sisters were doing was getting fucked up, “black-holed” they called it, and getting laid.

Cocaine and bath houses. PCP, Tuinols, black beauties, MDMA, ethyl chloride, hashish. Maybe it was that we all moved to Key West to deal with our sexuality, but all we could do was black-hole and get high enough so we could have anonymous sex in a dark room at a bath house.

When someone asked me why I was moving to Manhattan, I told them, “There’s only so long you can talk about suntans and blow jobs.”

It wasn’t until twelve years later, when I was invited to a “gay spirit” meeting in Tennessee, that I found what I’d gone to Key West for twelve years earlier. Gay men holding one another, looking one another in the eyes. Talking. Revealing what was in their souls. I cried the entire five days.

Manhattan and Columbia University helped me put myself back together. I began to meet gay men who had real lives, real jobs, made art. Of course, all this came with the deepening scourge of AIDS.

The other night after our weekly Dangerous Writing class, my partner Sage and I were lying on the couch together, talking about the class we co-teach and the writing that had been shared that evening. Dangerous Writing has become my new family. There’s this group of people whom I know so intimately, because really, what we’re all doing is going to our ghosts, and revealing our ghosts, outing our ghosts by writing about them. I’m the luckiest guy in the world really. My basement is a famous place where people come to tell the truth.

There is so much to tell you about my partner Sage. He’s a searcher, a Jupiter out there in the world so eager to understand all its mysteries. He’s a big guy with a big personality and a lot of love. And a real Italian beauty. He’s a singer, a performer, a publicist, a tattoo artist, and will soon be going back to school to study Chinese medicine. He’s younger than me by twenty-four years. I get scared for us sometimes as time passes. What’s going to come along. And of course then there’s AIDS and I had a stroke seven years ago. I’ve recovered but I’ll soon be sixty-eight and who knows what’s going to come along. But I do know in my heart, I’ve found my true partner. I would trust him with anything.

As I lay there in the big strong arms of my boyfriend that night after class, the fire going, Pat Metheny on the turntable, my nose snuggled into Sage’s armpit, I realized that my father had lost this long battle between us. I was in the loving arms of the man I loved. And I felt safe.

Interview by Scott Tankersley

Images and video courtesy of Lee Relvas

Like most people, I tend to stare at the wall, twirl my hair, and cook up fantastical visions of the future.

One of these fantasies involves an LGBT senior center that houses old queens, including Lee Relvas and me. As I’m spoon-fed applesauce by a young, gentle, soft butch-of-a-bear nurse in the rec room, I listen to my neighbor gab about the wild game of Bingo they played earlier that day. The microphone starts to feedback as as Nirvana’s “Negative Creep” fades into the background. The smoke machine lets out a long sputtering hiss. The spotlight clicks on and lights up the small stage at the front of the room. Lee canes their way up to the stage, grabs the mic, hits play, and the crowd of old queens begins to smile and cry.

Lee Relvas, who also performs as Rind, often combines music, textiles, drawings, and sculpture in their performances, and then disperses versions of these works via artist books and recordings. Through sound and live performance, Lee offers a unique, dissonant, guttural representation of an overwhelmingly chaotic world.

Lee inspires me to grow older, wiser, and more confused.

- Scott Tankersley

I often find myself living in other people's spaces for brief periods of time. I housesat at a friend's studio recently, a classic studio warehouse space that also had very similar dimensions to a black box theater. The lighting came from high above and created shifting halves of light and shadow.

Although there was usually no one around, I always felt like I was on stage. The light and shadow seemed to create amorphous rooms for me to move through and seemed to be breathing with my thoughts, adjusting their size and shape to my emotional state.

I went to the mall recently to get my ears pierced. It was a big one in Los Angeles, with a typical mall design with the big center atrium enclosed on all sides by three stories of stores. It was an airy limitless buying experience designed to deliver humans from one store to the next, to corral people to and from the food court.

But on the ground floor, there was a small black platform, probably twelve feet by fifteen feet, no more than a foot high. In the context of the mall, it seemed to be nearly useless. It didn't come with the directive to “chill out with a iced macchiato” like the oversized leather chairs or “take a load off and put all those shopping bags down here” like the huge circular benches. This platform was a stage, a place for performance, the one place in the mall where the space seemed unruly.

I sang show tunes and standards in a children’s choir as a kid. We performed in malls every Christmas season. When I saw that little stage, so many sensory memories came welling up inside me: my agitated stomach before singing a solo; my clumsy, heavy feet trying to remember the dance moves; holding the sweaty hand of the kid next to me; the erratic rhythm of the disinterested applause of the shoppers milling by.

The sensual and flexible space of this platform seemed miraculous in the rigid consumer context of a mall, but it's a miracle that’s luckily very repeatable.

It turns out you don't even need a platform.

The last four years have been waves of transition for me. I entered my thirties and moved to Los Angeles from Chicago, where I had lived for eight years. I tried to figure out how to make music and art without doing drugs, and I climbed out of an isolating depression whose only happy side effect was that it allowed me to make art and music nearly 24 hours a day.

In that solitude, there was lots of space to imagine voices and bodies surrounding me, so I built a world that was nearly under my complete control.

I made a couple of solo one-act operas with accompanying comic books that took the ephemeral flashes of radical happiness and ecstatic community-building I'd experienced in the various queer, feminist, and DIY scenes and made them stylized and baroque, curlicued them out in all directions to the far edges of what I could see.

But my vision always seemed eventually to hit a wall somehow, the wall that encloses any utopic space. So I began to make projects by closing my eyes and looking at what I could not see: the future.

I wanted to lay out my entire imaginary life from birth to death and see if I could divine any patterns there. I wanted my drawings and paintings to tell me what to do with my life next. The paintings and drawings told me to make more drawings and paintings.

I also attempted to look at what I could not see by radically adjusting the scale of my vision. In Exhaust Yourself, the series of oil spill embroideries I made in the aftermath of the BP Gulf oil spill of 2010, I thought that if we could only see the oil spill from the right angle and distance, uncapturable by any camera, it would spell out some arcane message to us.

In the Rind album also called Exhaust Yourself, I attempted to split my eye and my voice and take the perspective of every person and thing impacted by the spill—the ocean, the oil, the coral, the CEO, the driver. By attempting to give voice to all these differing forces, I hoped it would culminate in a chorus of voices, some at cross-purposes but all singing a dire warning that everyone would recognize and heed.

This too was a very circumscribed fantasy, a closed world.

I am moving from a position of certainty, be it utopic or dystopic, to uncertainty, which feels like inhabiting many places at once.

Feelings are large and they seem to inflate my body into different shapes. These shapes are neither stable nor coherent. The permeable space of a platform, and the porous rooms that light and shadow seem to build up and down, is elastic enough to hold and expand and collapse with the emotions that I want to communicate.

Light and shadow and a platform are old theatrical framing devices that give gentle directives to the audience's eye, but don't particularly limit it either.

To activate my feelings of incoherence, I started to imagine the world of the understudy in some struggling traveling theater troupe.

I'm understudying a bunch of roles in case any of the leads can't perform that night. I've memorized all these different parts and they’ve all started to jumble around in my head. I get confused which role is which and in what order the narratives occur. Some roles attract me more than others, and I'm not particularly convincing in any of the roles, but I still have this yearning to go on stage and perform.

I also started to exclusively make music on my computer to accompany my live singing. I summon the electronic understudies of flutes, pianos, violins, guitars, drums—the physical instruments I used to play, themselves understudies of heartbeats or birdsong.

To me, this doesn't point back to some original role, some original sound, but just causes me to look at the frame and see how malleable it is. Put a frame around something or someone, and that person or thing is under study. Let’s give it our attention.

Interview and videos by Igor Siddiqui

Cut-ups courtesy of Hyenaz

Hyenaz, a project by Mad Kate and TUSK, is a fusion of electronic music and performance art. The Berlin-based duo’s approach combines intellectual exploration with an improvised palette of expressive means, resulting in soundscapes, choreographies and appearances that are at once refined and rough. Hyenaz are creatures of ritual, frequently pursuing a path to creative freedom by following seemingly prescribed actions. Deeply inspired by their urban surroundings, they nonetheless emerged in the Czech countryside one winter, building a fire daily to keep themselves warm and inventing chance-based rituals through which their first lyrics were penned.

For this interview, which we conducted as a video chat, Mad Kate and TUSK proposed a round of cut-ups, a ritual in which a selection of printed texts is cut out, reassembled, and posed in the form of interview questions. The result is a series of free associations, personal reflections, and nimble improvisations that not only reveal how Hyenaz think and feel, but also that ultimately the pursuit of art is a search for questions.

- Igor Siddiqui

Cut-up is a literary technique for generating new content by manipulating existing text. Dadaist in origin, it was popularized by William S. Burroughs and subsequently appropriated by the likes of Julio Cortázar, David Bowie, and many others.

Texts:

Faggots by Larry Kramer,

A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes,

Great Expectations by Kathy Acker,

and four different poems by CAConrad.

Words by Clark Allen

Images by Clark Allen, Aubrey Edwards, Brad McCormick, and Julian A.

Video by Justin Gordon

At about 50 years old, skateboarding is this nation’s youngest athletic pastime. Were skateboarding a person who took reasonable care of his or herself, it would still likely be out there doing what it does. What other sport could the same be said for? Baseball, basketball, and American football would all be dead in their coffins by now.

With the greater percentage of skaters today being under the age of eighteen, it’s the only sport that remains a “youth sport,” and only recently has it come to wider social acceptance. And in New Orleans, where a large portion of the post-Katrina youth could find little to do but had a huge amount of space to do it in, skateboarding quickly grabbed a stronger foothold. As families tried to get their lives back into place, skating was an easy and accessible form of entertainment for kids.

In 2010, frustrated with the lack of a proper skate park in New Orleans, three friends named Joey O’Mahoney, Ally Bruser, and Mark Steuer decided to build their own. And so the Peach Orchard, also known as the Hippie Slab, was born, built on top of a large, barren concrete foundation in the Gentilly neighborhood, situated just between the 610 overpass spanning Paris Avenue and the railroad tracks that run parallel to the bridge.

For the following two years, a growing crew of dedicated skaters ceaselessly added to the park, and even more came to skate it. And then in 2012, it took just one day, a couple guys, and a bulldozer to tear the whole thing down.

This is the story of what it’s taking to build it back up again.

The Peach Orchard, fall 2011. About ten skaters criss-cross the concrete slab, taking turns on wooden ramps and a hand-built quarter pipe. A couple of teenagers push brooms around, collecting garbage and dumping it into metal trash cans. There are murals on the walls. It’s harmonious.

When trains pass, the conductors slow and wave as the kids try to pull out special tricks for them, hollering back at the engine’s whistle. People drag generators out for punk shows. Fully organized skate contests take place, complete with PA play-by-play announcements. Prizes for both youth and adult participants are donated by local businesses like the Preservation Board Company and Humidity Skate Shop. There are weekly potlucks: Red Beans and Rice Mondays. More and more people are willing and able to lend a hand to make the park a welcoming place for everyone in the community, skaters and non-skaters alike.

For the kids who skate it, the warmth and accessibility of the Peach Orchard is a direct contrast to the rest of their hometown.

“The kid here, all he has is some ledges up the street, maybe a five-stair. But he can only skate that for so long before he gets kicked out,” explains Justin Gordon, an eighteen-year-old skater whose popular skate videos show him shredding through the city. “On an average skate day, nine or ten hours, we'll run from the cops around seven times.”

Then, on May 14th of 2012, Joey received a phone call from a frantic young skater who was sure that the DEA had come to shut down the park. But it wasn’t the DEA; it was representatives of the Norfolk Southern Railroad Company, who owned the land along its tracks. Turns out that the park had been built, illegally, too close to the train tracks.

And just like that, twenty-five months of work was torn down in a matter of minutes.

Immediately after the Hippie Slab’s demise, the team relocated their efforts only yards away, this time beneath the 610 overpass, off Paris Avenue. The new skate park was dubbed Parisite, and the crew—Ally, Joey, Mark, and now Skylar—became official, forming a nonprofit called Transitional Spaces.

Together they began attending parks meetings, standing up to speak on their own behalf, and distributing pamphlets to prove their intentions: The park, while created for the purpose and love of skateboarding, hosts a grander vision—to build a community space for everyone.

This time around, Parisite was being built on city land rather than private property, providing greater wiggle room for some kind of compromise. People within the city lent an ear, and after about a year of meetings, Parisite’s official status finally became an agenda item.

As a proper written agreement is being drafted with the city, Transitional Spaces has been finding support elsewhere as well. They received $5,000 from the New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees through the 2013 Super Bowl’s Super Service Challenge, and after that, they were awarded $10,000 from the Tony Hawk Foundation.

And, a partnership with Tulane City Center has also been established: the Tulane City Center, which houses the Tulane School of Architecture’s Urban Research and Outreach Programs, has taken a great interest in the potential that Parisite has behind it.

The most transcendent idea behind Parisite is the idea of open inclusion and community involvement. Skating and working together foster that notion, especially in an impoverished community with a crime rate of landmark proportion.

“It keeps me out of trouble,” says Chuck, another skater. “Young black kids these days, and some white kids too, they get into robbery, burglary, just anything, weapons, stuff like that. My team, we never got into any of that.”

“You're not gang banging and stuff,” adds his friend Lance. “It's fun, and you have stuff to do.”

It seems obvious of course, but these concepts have been overlooked during other attempts at boosting the skate scene in New Orleans. At the same time the Transitional Spaces crew was working hard to fill the void that the destruction of Peach Orchard had left behind, Lil Wayne was also attempting to open up a skate park in the Lower Ninth Ward.

A collaborative production by many corporate entities including Lil Wayne’s “DeWeezy” marketing partnership with Mountain Dew, the Make It Right foundation, park designers California Skateparks, and brand strategists the GLU agency, the Trukstop Skatepark was heralded with a much-publicized grand opening that featured Weezy himself skating the state-of-the-art ramp alongside Paul Rodriguez and Theotis Beasley on September 27, 2012.

But, just weeks after the Trukstop Skatepark opened, it closed.

Apparently, the cost of insuring and staffing the park had not been factored into the plan. But not only did the people behind the multimillion dollar project falter at bureaucratic hurdles like insurance and adequate staffing, no one seemed interested in asking what the people who would use it might want to get out of it.

Meanwhile, at Parasite, Ally was busy organizing girls' skate nights for the ever-growing female skateboard crowd, and flyers appeared all over town calling for park design submissions and advertising mural painting contests.

To this day, the Trukstop Skatepark remains closed, literally locked up and officially off-limits to the kids in the neighborhood.

There is a lesson to be learned here. Without a bunch of enthusiastic people coming together to illegally build whatever they wanted, hauling in dirt, biking in tools, using old TVs as fill and chain link fencing as rebar, Parisite could not have been created. On the other hand, it could not have remained without learning that the attitude from which it originated is ultimately a broken record.

To use Skylar’s words: “What’s the old saying, ‘To a man with a hammer everything looks like a nail?’ Well, to a punk everything looks like a punk show. If you think of punk as a hammer, well, it’s good for certain jobs but it’s not good for every job…So, we think about the tools we’re bringing. Punk is going to be useful another day, another time, but not for bringing to those meetings.”

And he’s right. The success of Parasite is about putting hard work into a labor of love, which may call for an aggressive angle at times, but it’s also about growing up, compromising, and ultimately building something not just for yourself, but for everyone else as well.

Words by Silky

Images by Autumn Spadaro

Starring Silky, David, Cody, Nevah, and Gorgi

At first I didn’t think about passing. I was just interested in pulling off the cruise.

It all started when I was trimming pot in Northern California.

I made friends with a crack-head queen who happened to be an oracle of many mystical and absurd revelations. She was also a prolific butch bottom who shared with me the highlights of her roadside rendezvous in a velveteen van that cruised rest areas and XXX bookstores up and down the 1.

“Men suck men everywhere,” she told me, “at Wal-mart’s in the bathrooms and at scenic vistas in the front seats of beige sedans.”

In the men’s bathroom at a dog park in Daytona Beach, the writing’s on the wall. “If you want action, walk outside and rub yr dick—I swallow.”

I walked outside, looked around. But it wasn’t that easy. It was tricky to be discreet amidst the beach families and dog owners, and there was a big cop presence after sundown.

Finally, I caught this guy’s eye. I pulled my truck in next to his and we were window to window. We jerked off from our seats, watching each other’s faces through the glass.

Driving up Route 15 in central Pennsylvania, I pulled over at a scenic vista. There was a guy in a car, driver’s window down against the winter. His hand was hanging out in an upside down OK gesture that felt to me part secret handshake and part come hither. I walked back and forth in front of his car a few times before I stood at his window and asked him, "Hey, are you looking for some action?"

He wasn’t bad looking. If he were a teacher, he'd be a math teacher that also coached football. I could see him rubbing on his dick through his pants. “It’s a little out in the open here.”

He was nervous, thinking he was talking to a teenage boy. I was turned on in a way that I’d never been. I couldn’t bear to take no for an answer.

What’s the town past Lake Charles on I-10? The truck stop there is so dirty south and the town smells like sulphur. There is a truck stop there, the kind that has hot showers and a casino and 24-hr diner. The gift shop sells CB radios, real-tree hats, bumper stickers, and gigantic plastic mugs for coffee.

It took a while, but I made eye contact with a scary redneck trucker. Flannel, denim, beard, cigarette hands, baseball cap, pushing 50, he followed me into the bathroom, which had two stalls and was very tidy. I sat on the toilet and unzipped his jeans. He grabbed me by the ears like they were handles. He also patted my hair like a beloved cocker spaniel while I worked on him. As if to say, “Young man, you are doing a very good service for all the truckers of America.” And I felt like: Yeah, I’m doing my part to keep the industrial machinery moving along.

As soon as he got off, he left without a word.

There’s a patch of highway near Harrisburg, PA, that has a sleazy strand of X-rated bookstores. Clerks smoking cigarettes behind desks in rooms full of dusty old vibrators and hallways with black plywood porn booths and red lights that cast only shadow. There is a clandestine sense, cloaked and quiet. Time travel to 1985.

Inside a buddy booth, I opened a mechanical window and could see a muscly, bearish guy, pants down, jacking off to something faggy. He brought his boner up to the window and stroked it.

I rubbed mine, a little silicone flop that looks like a fancy dog toy, then I turned around and spread my ass up against the glass for him. He did the same for me.

He waved me in and cupping the back of my buzz cut on my knees in front of him he shot off into my mouth, fast and hard, in just a few strokes. I nodded and left before words blew my cover.

In New Orleans, I occasioned upon a really strung-out video arcade with a movie theater containing about 20 seats and some black booths lit blue. In the front, there was advertised a few things of interest: Glory holes! Poppers! and Cell phones!

Glory holes! I watched a big guy with a little dick give head to a kid who kept his headphones on and texted the whole time. Right before he came, they both shared the big guy’s poppers.

There was a stoic cowboy in the main theater who wouldn’t make eye contact. The movie playing was of a strangely tender Latino guy making love to a lady. I moved to sit in front of the cowboy, rubbing myself through my pants. Eventually, I could hear him jerking off behind me. Every so often, I’d look back and let him know I was willing, and I got the sense that it made him feel violent.

I have a cute truck stop gimmick. I put on my backpack and hoodie and walk through the herd of 16-wheelers idling in the dark. Only once has it worked; a trucker flashed his lights and I climbed into the passenger seat.

"Do you fuck?"

"No, just oral. $15."

He puts on music and here we go again.

On Route 71 outside Austin, there is a gorgeous shack of a porn hole. I got no action there, but the woman behind the counter was perfect. Leathery, long blond hair, ashtray voice. She’s in conversation with a customer across the room. "Apparently now in California they’re making the actors wear condoms! What next?! The girls have to wear goggles??"

She sees me near the back room and says, “You want some tokens, sir?”

I pay and she says, “Ok, perty, you enjoy.”

When I’m leaving she calls out, “Alright, darlin! You have a good Christmas! You come back again, ok?"

Then, down off Slaughter Lane, I passed a two-story arcade that was packed on a Tuesday night. I gave this guy head. Fat guy. Good looking. Kind of funny, making jokes about other guys in the place and really friendly and normal.

He wanted to fuck and I let him finger my asshole but his hand found its way to my other hole instead. I was bleeding and not wearing a tampon and I thought, shit, but I kind of diverted and finished with the blowjob, wondering what he thought. He came and then he left and I saw him in the bathroom washing his hands. I thought for sure he saw the blood and figured it out.

But a while later he came back and said, “Dude, you’re so hot. Sure you don’t wanna fuck?”

He was rubbing my soft pack outside my pants and I said, “No. I don’t like to get touched.”

The sleaziest one was the best. Such a shit hole, I passed it once on the access road and even in the parking lot, I couldn’t tell if it was a sex shop or a meth lab. There is a raspy feathered-hair fag behind the counter who barely eyes me as he hands me tokens. Everything in the place is wood paneled and the hallway is carpeted and dim. There are only five booths and half are broken.

I pick the one in the back corner and start up a twink video. It’s old too, a time capsule inside a time capsule. All the boys on film are probably dead.

Then this guy comes in. He's like a cross between Ned Flanders and Dan from Roseanne, a chubby dad-type in a sweater vest, round and a bit burly with a big mustache and glasses. If it doesn’t sound hot to you, we don’t have the same taste. He reaches out and rubs my cock. I’m scared to let him, but for just for a little bit, I do. It’s a leap of faith. The whole point is the leap.

I try to get on my knees where he can’t find my package but he holds me up and kisses me, runs his hand under my shirt, grabs my hair. Then I’m stroking his cock and then I’m sucking it.

He comes down on the floor, joins me there, pulls off my shirt, sucks on my nipples, kisses me, and guides my mouth to his dick again. When he’s almost gonna blow, I tell him to cum on my ass. He pulls my pants down just enough and slides himself up between my ass cheeks, jerks it off against the hole and cums all over my ass and back. It’s dripping down my crack and I’m saying, “yea daddy yea daddy cum on me” while he does. I get off too, rubbing on that soft pack.

He pulls me up and says right up to my face, “when can daddy see his boy again?”

I tell him, “I’m not from around here,” and I duck on out.

Words and images by Eleanor Moseman

Eleanor Moseman is an American photographer who has been bicycling across Asia since the spring of 2010, documenting what she calls “hidden communities, disappearing traditions, and cultures in danger of being erased.”

To do so, she has logged more than 15,000 miles through seven countries—more than halfway around the world—alone with her camera, her backpack, and her bicycle. For four years, she has dedicated her life to creating vibrant, intimate portraits of the people she has met in Tibet, China, Bangladesh, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere.

In the following pages, Eleanor shares with us what it can be like for a woman alone on the open road, paired with her photographs of the people she has met and the landscapes she has inhabited along the way.

- Diana Welch

I wake up before everyone, on the porch with the three young girls I had giggled into the night with.

The sun is just beginning to light the sky to a saturated navy blue. Heat is all I can think about at this point, even with the cool desert breeze going over my dry and burned skin. The few moments before pulling myself up from the sleeping mat, I take a few slow deep breaths and give myself my morning pep talk. It will be okay, today will be good, I will not suffer too much; I will stay alive and find a safe place to stay for this evening. I will listen to music and think about things that need to be thought about. I will work through some of my inner demons and acknowledge my insecurities.

I miss my family. I miss my friends. I feel good, I feel strong … I am strong.

Yesterday: the eldest sister braids my hair. It hadn’t been washed in a few days and needs a comb run through it. When we are sitting on the patio, about a dozen of us, she grabs her comb and comes to sit close next to me, letting me know what she wants to do. I smile gratefully and nod yes and take my rubber band out of my braid. I begin to finger comb the plait out and I then feel her hands run through my hair, fingertips gently brushing against my scalp.

My eyes begin to water and I hold back tears. My eyes are leaking, there is something I’m feeling that I’ve never felt before, an emotion that seems recognizable yet so distant and strange. I have been extremely emotionally neglected. I have gone more than a year without intimacy. I’m not talking to a sexual sense; I’m talking when you share a moment with another soul when you let your guard down. You allow them in. You share a connection.

I have to hold back from sobbing as she runs her hands through my hair, then the comb, but as she braids my hair I want to fall back into her and be held. This seems so out of character, so strange for a woman that goes days, weeks, months thinking—and more importantly convincing herself—that she doesn’t need so much human interaction. That she is a loner.

I wake the younger sister as I put my bag on my bike and she leads me to the road where her sister and mother escort me. It’s been an emotional twelve hours and as I hug the sisters and then the mother, I again hold back tears. There is something in their eyes, something that their soul speaks … it seems we all have some sort of suffering and past words and language barriers, we are all speaking to one another. I call her “mother” and the two “sisters” in Uzbek and thank them. Holding back the tears I ride off towards the bright orange sunrise. I can’t look back … I can’t bear to see their faces. There is a part of me that wants to stay, to have company, to feel a connection, love, and tenderness.

The day is uneventful as I’m back on a main route to Bukhara. I notice the traffic begins to pick up and the heat gets nearly unbearable again. Stopping for water and shade as much as I can but the shade is becoming minimal.

At sunset I begin looking for a place to camp. It’s all open desert with occasional petrol stations. The traffic slows down and I ride later into the night than I should; it’s not smart to night ride, especially on a highway.

About 80 km away from Bukhara I see a petrol station. It’s brightly lit and I could see it a few kilometers away. To the left of it is an abandoned building. I am still in the middle of the desert. There is nothing out here except some desert shrubbery and barely trees. I’m tired. I’m exhausted. I just want to lie down and sleep. I’ve been going for over twelve hours now.

I ride past the petrol station and see there is a mechanic working on a truck outside and no one else. Stopping, I look out into the landscape towards the abandoned building. There is always a fear in me of camping too far off from a main road. Because it’s a main road, there is a likely possibility of having night visitors. If it weren’t a main road, I usually have less concern. My rationale is if I’m close to the road, if I have problems, it’s easier for me to get help from possible traffic.

Standing on the side of the road, taking a moment to stare into the skies above and noticing how black it is, everywhere. Except for the stars, the moon, and the petrol lights.

I find a place to take my bike off the road and into the sand. Pushing my bike just to the edge of where the petrol lights hit, probably the length of a half a football field, I wait to see the attendant go inside or to not be visible.

Pushing the bike through the sand; there is no way I can make it to the abandoned building. I decide I’ll just lean the bike against a bush and roll out my sleeping mat.

Let me just state NEVER do this in the desert. After what I saw in the early mornings, it’s very unwise to sleep in the open desert without protection from spiders. When you’re exhausted, sometimes the brain isn’t up to par.

After lying down for about fifteen minutes I notice a flashlight. The attendant has spotted me and he’s walking towards me. He then turns back. I assume I will be okay. He’s given up. No. Now he drives a jeep over to me.

He’s a very large man. Asks me what I am doing and tells me I can sleep in the petrol station. I don’t want to. I’d rather stay out here. He’s insistent on it. So, with very little light I try to pack up my stuff without too much of a hassle and push the bike to the petrol station.

I follow him and roll my bike inside the garage and he directs me to a couch in an interior room next to the garage. I sit down and he explains he will be outside working. It’s around 10 p.m. I lie down. The room is boiling. I wish I were outside where it’s cooler.

He pays another visit shortly and puts a blanket over me. You’ve got to be kidding me. I’m like a roasting piggy now. What’s worse, the blanket is making my skin crawl. It feels as if my skin is moving and being bit. This is horrendous. As I hear him banging and working on the truck outside, I throw off the blanket and mutter some words about him being an idiot and this filth and go to the garage. I grab my tent ground cover and go outside. We make eye contact and I explain with hand motions that I’m going to sleep outside next to the garage. I find a place that is shielded by the bright lights.

My skin is no longer crawling and the cool desert breeze dries the sweat off my body within just a couple of minutes. I couldn’t ask for anything better, minus the lights and the constant mechanic’s sounds. There are also brief moments of conversation. My senses on full alert, I awaken often but not for too long. I figure if I can just get a few hours I’ll be okay for the following day. Only 80 km.

Although, every time I wake up I notice my body clenching up more and more from the cold. The temperature is dropping fast and the desert wind picking up. At first it felt good but now it’s beginning to get cold. The shivering begins and I apprehensively get up and grab my ground cover. Going back through the garage, I put my ground cover back in my bag. My bike is packed and I’m ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

All I smell is oil, gas, and dirty human. You know that smell of unwashed linens. I lie down on the couch.

I wake up, it’s around 3:30 a.m., and I notice the noise has stopped. The lights outside have dimmed. Finally, I can rest my head a little and get some sleep.

No. Someone is walking outside. There is the man’s silhouette in the doorway. He had been checking on me throughout the night but at this moment I knew something was different. He walks slowly into the room and sits on the couch, next to me. I can hear him breathing and see him looking at me. He leans in and grabs my chest with both hands.

I grab his hands and push them away from me. In my head, I am thinking, Here we go again, how am I going to get out of this one?! Previously, there had been people within shouting distance but this time, there was no one else around. Moseman, you’ve been here before, stay calm, cool, don’t alert him … you’ll get through this.

I stand up and go towards my bike, and he stands clumsily and gets in front of me and grabs my chest again. I place both hands on his chest and push him away from me, shaking and trembling but trying not to show the fear. He’s at least five inches taller than I and large. All I can imagine is a terrible situation, being crushed under his gigantic body smelling of oil, gas, grease, and unwashed hair.

“No, get away, I’m leaving,” all said in English. I haven’t got time or patience to deal with fumbling over Russian with another pervert.

Grabbing my bike, I ride a kilometer away from the station. It’s pitch dark and I wait on the side of the road and I know I have at least two hours before I have any possibility of light.

It’s unsafe to try and hitch at this time of the night. Anyhow there is no traffic.

I sit on the side of the road, eat a little naan and peanut butter, and relive the past 48 hours. How things can change.

Around 4:30 I begin walking my bike and riding when I can. I’ve let my eyes adjust and it’s not too bad.

Video by Acid Sweat Lodge

Music by Stephen Hamm

Psychedelics are illegal not because a loving government is concerned that you may jump out of a third-story window. Psychedelics are illegal because they dissolve opinion structures and culturally laid down models of behaviour and information processing.

They open you up to the possibility that everything you know is wrong.

- Acid Sweat Lodge

Interview by Diana Welch

Images by Hazel Hill McCarthy III, Douglas J. McCarthy, Lewis Teague Wright, Drew Denny, and Eric Nordhauser

Starring Genesis BREYER P-Orridge, Dah Dgbeninon, Sardou (Emmanuel) Dgbeninon, and Hypolite Apovo

Vodun derives from the word "vodu" which means spirit, or divine essence, in the language of the Fon people of Benin, a West African country that lies between Nigeria and Togo on the Bay of Guinea. The belief system of vodun, which has been around for centuries, remains unaffected by the pervasive Christianity, unlike its varied offspring, including Hatian Voudou, Louisiana Voodoo, and the vudu of the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico.

In the vodun religion, there is a single divine creator, known variously as Mawu or Nana Buluku, that is an androgynous being who embodies the sun and the mooon, female and male. Countless orishas, or manifestations of this creator, influence all aspects of life. For believers of vodun, the spirits of the dead live side by side with the world of the living.

As has been well documented, around the turn of this century, cultural engineer Genesis P-Orridge and artist Lady Jaye embarked on their Pandrogeny project. Using plastic surgery, hormone therapy, cross-dressing, and altered behavior, the two beings merged their identities to create the amalgam being, Breyer P-Orridge, challenging the limits of personal identity and true love. After Lady Jaye’s passing in 2007, the project took on an inter-dimensional form, with Genesis representing the amalgam in the physical world and Lady Jaye representing Breyer P-Orridge in the beyond.

Recently, Genesis teamed up with longtime collaborator, the artist and filmmaker Hazel Hill McCarthy III, to film the documentary Bight of the Twin in Ouidah, Benin. Ostensibly an exploration of an annual festival celebrating one of this world’s oldest religions, Hazel and Genesis discovered something much more mystical, and personal, along the way.

- Diana Welch

“In these festivals in Benin we believe we see so clearly a fabric of art, function, expanded consciousness, devotion and ecstatic revelation interwoven, indivisible from daily life and weaving a non-verbal Astory that might contain the greatest revelation ever told.”

- Genesis BREYER P-Orridge

DW:

Can you talk about the influence voodoo has had on Genesis’ work?

HHM III:

Lady Jaye was initiated in the yoruba religion shortly after meeting Genesis, and Genesis and Lady Jaye honored Legba, the god of mischief.

Genesis’ work, in its entirety, is vodun. It’s a way of life, the duality of life and death, change and stability, fire and ice, calm and chaotic—constantly in tangent of two halves seaming into one. This is seen in practice thorough he/r work with Lady Jaye.

Coum Transmissions is also a great example of Genesis’ vodun. Practice through ritual and ceremony to conjure up a moment of activation.

DW:

Before you and Genesis left for Benin, what were some of the conversations you had about your intentions with the film?

HHM III:

The film was loosely based on my fascination of spectacle and performance that makes up the pageantry and beauty of the costumes worn by the priests and spirits I had seen documented at the annual vodun festival in an article I read in the Guardian in 2009, I think.

The following year, Genesis and I were in Kathmandu. I arrived there straight from England, where I had been helping to care for my father-in-law who was dying from asbestosis and associated lung cancer. Literally cleaning shit from his ass.

Whilst in Nepal, Genesis suffered a severe gall bladder infection and was rushed to hospital in a critical condition. Sitting by he/r side in hospital I said, “if you make it out of here alive, we will travel to Ouidah, Benin, for the annual voodoo festival to find our parallel selves.”

S/he agreed, and we set the date for the January after he/r retrospective at the warhol museum.

DW:

One of the things that first stuck me about this project was the idea of revealing the joy and natural interconnectedness in an ancient religion that so much of the Western world regards as frightening, foreign, and dark.

It seems to me that the intention of the film is really in line with the current mission of the famous Benin priest, Dah Aligbonon Akpochihala, who was quoted in that same Guardian article saying, “we need to bring voodoo in from the dark.”

Did you meet him while you were there?

HHM III:

We did not meet Dah Aligbonon. We met with Dah Dgbeninon, who is father of the pythons. It was his son, Emmanuel “Sardou,” and his best friend, Hipolyte Apovo, who were our fixers and translators during filming and are now dear friends of ours.

Amazingly, as I went back over old links and research, I realized that within the very Guardian piece that was the impetus for my fascination and further exploration of vodun, I found Hipolyte Apovo was quoted about vodun. It’s what Genesis and I have come to call the “of course factor” … an endless stream of serendipitous events that have come to be a part of the process of this film.

DW:

So, initially, you set out to make a film that investigates the origins of a misunderstood and often maligned religious practice. But, while you were there, serendipity struck and Genesis was reunited with Lady Jaye through a series of rituals and sacrifices.

When I heard that, my mind was pretty blown. Talk about interconnectedness.

How did that come about?

HHM III:

Well, of course, the “of course factor” seamlessly streams through this film process. There was a reason to visit the cradle of voodoo in the sense that it was an idea, a feeling that kept gnawing at the back of my brain and tugging at my soul. Genesis felt it, too. We knew we had to investigate. I had no other intentions than to document the annual voodoo festival and the people who partake in its endeavors.

With Genesis by my side, we were to ask questions and soak in what we learned. But what started with a benign look at voodoo became an intense, intimate participation in the practice. We discovered that Benin has the highest national average of twins per birth (27.9 twins per 1,000 births). Twins are treated as special and everything must be shared equally between them. If one of the twins dies, the surviving twin has to carry around with them a small carved replica of their dead brother or sister, which has to be dressed in identical clothing and given a small bit of the same food.

The dead twin is not described as dead but “has gone to the forest to look for wood.”

DW:

Genesis recently mentioned that they had been given the “fetish name” of Jou Jou.

Can you talk a little bit about what fetish means in this context? Of course, when I think of “fetish,” it is something very different. Or is it?

HHM III:

The word fetish derives from the French fétiche, which comes from the Portuguese feitiço ("spell"), which in turn derives from the Latin facticius (“artificial”) and facere ("to make"). An inanimate object worshiped for its supposed magical powers or because it is considered to be inhabited by a spirit.

- Oxford Dictionary definition.

Likewise, the fetish, or bocio (empowered corpse) in the language of the Fon tribe, is believed to function as a mediator between the visible and the spiritual world.

Bocios are objects meant to remain enigmatic and obscure, to hide meaning and purpose from foreigners and non-locals.

DW:

Benin is known as “the cradle of voodoo.” More than half of the country’s nine million citizens practice the religion. What happens when everybody gets together? Is it celebratory? Somber?

HHM III:

When the city comes together to celebrate, it is music, singing, and rejoicing. There’s a proud bravado and ownership in the air, an uninterrupted and unabashed celebration of life—vodun.

Dah Dgbeninon, without hesitation, welcomed us into his house and treated like family. He shared with us a divination ceremony of love where we partook in the sacrifice of two chickens to commemorated Genesis and he/r twin’s successful connection.

On the day of the annual vodun festival, he shared with us a sacrificial goat to commemorate the blessings of the people of the village during this ceremonial time.

Words by Rebecca Bengal

Images and audio courtesy of Mumia Abu-Jamal and Stephen Vittoria

The facts of Mumia Abu-Jamal’s public life are well known:

Charged with the killing of a Philadelphia police officer in 1982, Abu-Jamal spent more than three highly contested decades in solitary confinement on death row in Pennsylvania, while maintaining his innocence and the wrongfulness of the accusation. He became a veritable icon for a movement centered on an overlapping spectrum of issues: human rights, racial prejudice, fair trials, abolition of the death penalty, and American imperialism.

Everyone from Amnesty International to Nelson Mandela to Angela Davis to William Styron rose eloquently to his defense.

When I first became aware of Mumia and his story, his name was part of a rallying cry, he was a stencil, a symbol, a slogan on the signs at protests that friends of mine organized that some of them endured twelve-hour bus rides to join.

Free Mumia.

It was a phrase we heard so often it functioned doubly as a bitter joke. “Free Mumia” was equivalent to “Peace in the Middle East.”

Deep down, we thought it would never happen.

And it didn’t. Or, it hasn’t yet.

Though his death sentence was lifted in December 2011, Mumia Abu-Jamal, now fifty-nine years old, continues to serve a life sentence in prison.

Since his incarceration in the summer of 1982, three other individuals have been executed in the state of Pennsylvania; by comparison, the state of Texas has executed 500 people.

Even the most charged, oft-uttered words become simply words at some point, and the danger inherent in transforming someone into a symbol of a cause is that they can cease to become a person.

Mumia: the controversial journalist and author. Mumia: the former Black Panther. Mumia: the wrongly accused. Mumia: with the long dreads and glasses; hair of a rebel, countenance of an intellectual. But rarely, Mumia: the fully dimensional person.

What’s revelatory, then, about Long Distance Revolutionary, a documentary film about Abu-Jamal released in 2013, is that the film dwells not on the details of the case, but attempts to present a definitive life story: Mumia the man, Mumia the writer, Mumia the activist.

What is most affecting and heartbreaking about the film is the engaged, complete portrait it presents of an emerging thinker and revolutionary, offering glimpses of that stolen life and what might have been, reflections by Mumia’s sister, family, and fellow activists.

When filmmaker Stephen Vittoria first met Abu-Jamal, he’d already been reading his essays and books for years. “He was one of those—along with Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky—who was on my shelf of people to read and really listen to … I thought the arc of his writing was starting to deal more with American imperialism than simply the industrial complex and the American prison industry. All these elements were in his writing in a very personal way, it was all embodied in this one man.”

As their postal correspondence developed into a collaborative friendship, Vittoria was allowed to visit Abu-Jamal in prison, spending up to six or seven hours at a time, discovering Mumia’s rich sense of humor.

“He hasn’t had cable very long but now he does, and his favorite TV show is The Walking Dead—and the irony of that isn’t lost on him,” Vittoria says. “And he does an amazing impression of George Bush, the younger moron. The last time he did it, I was there with a friend and we were tearing up, we were laughing so hard—it was a noncontact visit, so we were speaking through Plexiglas, and Mumia stands up and does his whole W. thing, it was just a really odd juxtaposition.”

A generation has elapsed since Mumia’s imprisonment. His three children—Lateefa, Mazi, and Jamal—are now grown-ups; he is nearing retirement age—a concept that does not apply to him. He is an award-winning journalist who has published several books, numerous essays, and he broadcasts regular dispatches on Prison Radio—on Chiapas, on the lingering impact of Brown vs. Board of Education, on fellow thinkers, like Dr. Vincent Harding and Maya Angelou. With Stephen Vittoria, he is currently completing a new book, Murder Incorporated, which aims to examine “the myth and reality of American history—a history founded in genocide, nurtured through slavery, and then perpetuated by never-ending war.”

“Ask Iraqis or Afghanis today how they feel about Manifest Destiny,” Mumia writes in the book. “In fact ask an American about Manifest Destiny—although you’ll probably have to explain it to him first. And then pick an atrocity, any atrocity. John Q. Patriot won’t like it, but as Douglas Popora writes in How Holocausts Happen—The United States in Central America: ‘Although the American people disapproved of what was going on, they did not much care about it either.’”

The struggle Abu-Jamal has endured, largely in solitary confinement, is deep, something that belies the outgoing nature he presents to the world. Says Vittoria:

“I think his gregarious personality is absolutely for real: His spirit has transcended the tragedy of his stolen life. At the same time we know he must have those midnight hour moments; he knows the horrific hell he’s in, but he doesn’t dump his own victim story on others.

“It’s incredibly spiritual. That’s why they haven’t beaten him.”

No. 5

Coming Fall

2014